A thought on unlearning and reimagining difference, by Mark Vernon

I know a psychotherapist who tells this story. One day, a new patient walked into her consulting room. He sat down, looked at her uneasily and said: “I’m sorry. But I can’t speak openly with a black therapist.” He was white. Without a pause, she replied: “Thank you for being honest. Now I know we can really talk.”

The incident is striking not just because of the psychotherapist’s presence of mind and her ability to tolerate the aggression. Nor is it that the new patient’s confession put the first hurdle to good therapy right in the middle of the room. Further, the exchange was valuable for the therapist, as well. His shameful remark enabled her to be honest about any of her presumptions. She might learn something, too.

I value the story because it holds out the possibility that when differences meet, and aren’t kept as elephants in the room, unexpected combinations and revelations might emerge. Transitions catalyse and light reaches unlit corners.

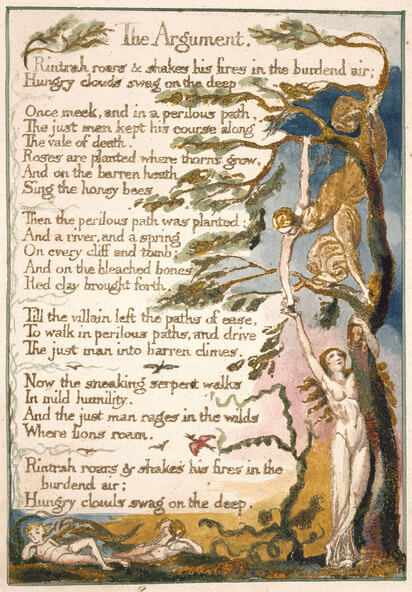

“Without contraries is no progression,” observed William Blake. He was pointing to the energy that is present when, like the north and south poles of a magnet, diversity makes for tension that needn’t fling people apart but might draw them together, because all are drawn to more.

Here’s a second story, told by the writer Annie Dillard. In her essay, ‘Teaching A Stone To Talk’, she describes a man called Larry whom she sees every day, trying to listen to stones speaking. Literally. It seems a kind of madness, the opposite of the sane scientist who would never exhibit such behaviour.

How should she respond? With pity? Or better, with a readiness for a new perception. Dillard thinks again. Aren’t geologists trying to speak with stones as well? Aren’t they yearning to hear their ancient stories? Larry and the geologists are not only not so different, Dillard realises, as a single humanity comes to mind. Across the divide, they are united in a common love.

A third account of difference, this time featuring the writer C.S. Lewis and his great friend, Owen Barfield. Lewis called Barfield his “second friend”, and in one book which he dedicated to Barfield, included the epigraph, “Opposition is true friendship”. The thought is from ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’, by William Blake.

For Blake, the contraries with which human beings can antagonise one another are actually gifts, when freely received, and so are acts of friendship. They might provoke not rage or fear, but discernment and novelty.

Lewis valued Barfield for that reason. He advises that everyone needs a “first friend”, with whom any differences are straightforwardly eclipsed by affection. But, in order to grow into life, everyone needs a “second friend”, too. Disagreement and irritation will feature in this relationship. But also love and a recognition that a future is unfolding that the second friend enables, and with which the second friend shares.

Difference is our theme for unlearning and reimagining at the Realisation Festival 2023. With the gathered speakers and participants, we will have rich resources for considering contraries across the personal and political, the systemic and the soulful. Tensions will be present. But love will be, too, along with a shared desire to become more than we are for the future.

Mark Vernon, with Pippa Evans, is coordinating the programme for Realisation 2023.